To boldly go where no diplopodologist has gone before

New genera and species highlight how little we know of millipedes

In August, 1768, when James Cook set sail from Plymouth harbor on HMS Endeavour, much of the southern half of the world was uncharted. By the end of his voyages, the globe was understood substantially as it is today. His was also a voyage of biological discovery, with ship naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander collecting about 30,000 dried specimens that included almost 1400 species new to science.

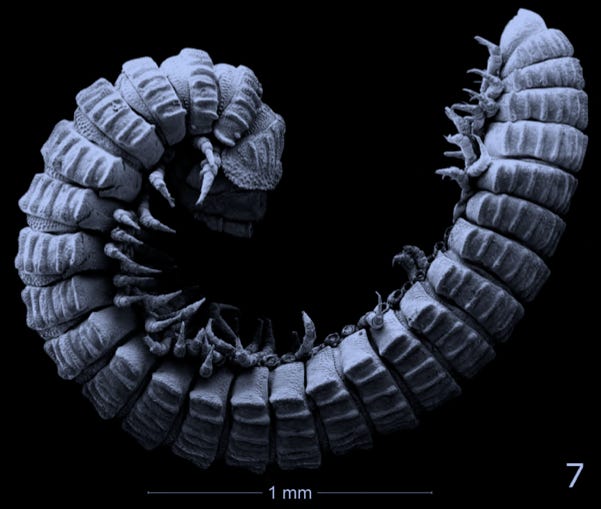

Maraplia napa, female, lateral view. Source: Shear and Marek (2022b). Note: head shown in separate image in publication.

It's easy to think that the great age of exploration is over. There are no continents or mountain ranges left to be discovered, and our knowledge of the earth is impressively detailed. We know that the diameter of our planet is twenty-six and half miles greater at the equator than measured pole to pole, and that the length of days on earth are increasing by 1.7 milliseconds every one hundred years. But those who believe the age of exploration is relegated to the past are overlooking biodiversity.

What we know of the inhabitants of earth is dwarfed by our ignorance. The two million species discovered since the beginning of modern taxonomy in 1758 has only scratched the surface. Millions and millions of species remain unknown to science. Thankfully, like Captain Cook, there are intrepid taxonomists busily charting the biosphere, making one astonishing discovery after the next.

One might suppose, for example, that a group like millipedes is well known in North America, but one would be wrong. In a recent publication, the sixth in a series, William Shear and Paul Merek described six new genera and thirteen new species of millipedes of the family Striariidae from California, Oregon, and Washington. The diversity of morphology exhibited by these new genera and species is simply spectacular. Striariid species occur in both the east and west, but the Pacific coast, from San Francisco Bay to Vancouver Island, is proving to be the center of diversity for the family.

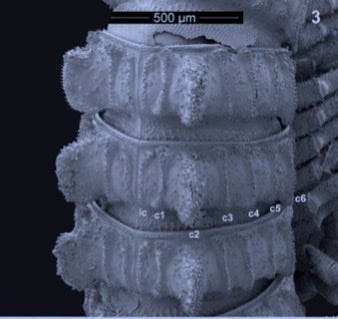

Stegostriaria dulcidormus, midbody rings, oblique dorsal view. Note enlarged second crests. Source: Shear and Marek (2022a), Zootaxa 5094: 464.

Among many interesting features, these millipedes have a dozen parallel, longitudinal crests on their backs, sometimes elaborately ornamented, sometimes with particular crests exaggerated. In some, the lateral-most crests are horizontally extended. In another genus recently discovered Shear and Marek, the second of the six pairs of crests are elevated, conspicuously larger and more prominent than the others. Reminded of the double row of armored plates along the back of the dinosaur Stegosaurus, they cleverly named the new genus Stegostriaria.

Triseria rex. Gonopods, anterior view (gst=gonopod sternum). Source: Figure 21 in Shear (2020)

Like other millipedes, males of the new species use extremely modified walking legs to transfer packets of sperm from an opening on their third body segment to females. Leg pairs 8 and 9 start out as normal legs, then, through a series of molts, transform into incredibly complex sexual organs called gonopods. It’s difficult to describe the more elaborate gonopods with words. Let’s just say I’ve seen grand chandeliers in log homes made from stacks of antlers that looked less complicated. In some millipedes, the gonopods are used to stimulate the female prior to mating, and in some it is used by a male to scoop out sperm left earlier by a different male, before depositing his own. The Kama Sutra has nothing on millipedes when it comes to creativity.

Why, you may ask, have such amazing creatures remained unknown until now. Three factors seem obvious. First, millipedes lead somewhat secretive lives. Second, there are too few experts for the number of millipedes awaiting discovery. And finally, in this case, size has something to do with it. The newly found millipedes are among the smallest on earth, at just 3 to 5mm in length.

When Captain Cook set sail, the northern half of the globe was reasonably well mapped. Taxonomists, out to explore earth’s flora and fauna, face a much greater challenge. Less than 20% of species have been charted, millipedes being a good example. The 12,000 or so named millipedes are a small fraction of an estimated 50,000-80,000 species. As we face an uncertain environmental future, no preparation could be more basic than taxonomy’s mission to discover and map the species of the biosphere. And as an added bonus, like Captain Cook, Banks, and Solander, we will be rewarded with incredible discoveries.

Acknowledgment

I thank Dr. William A. Shear for permission to reproduce images from his publications.

Further Reading

Shear, W. A. (2020) the millipede family Striariidae Bollman, 1893: I. Introduction to the family, synonymy of Vaferaria Causey with Amplaria Chamberlin, the new subfamily Trisariinae, the new genus Trisaria, and three new species (Diplopoda, Chordeumatida, Striarioidea). Zootaxa 4758: 275-295. [note: this publication is not open access]

Shear, W. A. and P. E. Marek (2022a) The millipede family Striariidae Bollman, 1893. V. Stegostriaria dulcidormus, n.gen., n.sp., Kentrostriaria ohara, n.gen., n.sp., and the convergent evolution of exaggerated metazonital crests (Diplopoda, Chordeumatida, Striarioidea). Zootaxa 5094: 461-472.

Shear, W. A. and P. E. Marek (2022b) The millipede family Striariidae Bollman, 1893. VI. Six new genera and thirteen new species from western North America (Diplopoda, Chordeumatida, Striarioidea). Zootaxa 5205: 501-531.

If you are interested in Captain Cook’s voyages, I highly recommend Tony Horwitz’s Blue Latitudes, Henry Holt & Co., New York, 2002.