Saving Systematics: Taxonomy does not exist to identify species

Those content with "minimalist" taxonomy and DNA barcodes are welcome to know as little as they wish, so long as taxonomists are permitted to learn as much as they can

The current trend toward a molecular-based taxonomy, with a decreased emphasis on descriptive taxonomy (i.e., revisions and monographs) is a symptom of a deeper issue: a basic disagreement regarding what taxonomy is; what its purpose and mission are. When the ultimate destination of taxonomy is agreed, then the best means to get there become clear.

The Microsculpture exhibition, featuring close-up photographs of insects by Levon Biss, has wowed museum visitors around the world. Were these posters displaying DNA barcode sequences for the same species of insects, would the public have a similar reaction of awe? It is the unexpected detail, diversity, complexity, uniqueness and beauty in these images that surprise and capture the imagination. Using molecular data to identify millions of species about which little or nothing is known is self-imposed ignorance and a travesty of taxonomy.

Source: http://microsculpture.net/exhibition.html

For more information and prints of Biss’ photographs: levonbiss.com

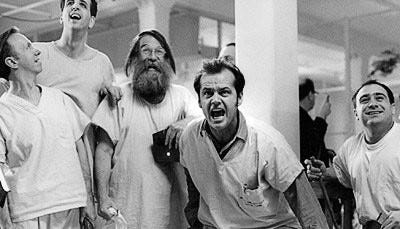

To a shocking degree, taxonomy’s agenda is being dictated today by consumers of taxonomic information. The inmates, as the saying goes, are running the asylum. There is no question that environmental problems, conservation challenges, and accelerated rates of extinction mean that identifying species is critically important and urgently needed. It is not surprising that those only interested in identifying species would eagerly accept shortcuts that appear to give them what they want faster, cheaper and easier than supporting the serious scholarship and rigorous research associated with traditional taxonomy. Those seeking quick and easy answers, however, should be careful what they wish for.

It may seem paradoxical that we can identify species and that, at the same time, species do not exist to simply be identified. This is because, in taxonomy, species are hypotheses that make predictions regarding the distribution of specified characters. As it happens, it is generally possible to infer that a species exists based on the average amount of genetic difference between known species in the group to which it belongs—but this is a starting point, an informed speculation, not a conclusion. A testable hypothesis is still required and there are exceptions. Documented cases exist where the amount of genetic variation within a species exceeds the average amount of difference between other species in the clade to which it belongs. So, simple measures of similarity are suggestive, pointing to possible species in need of further investigation. Confidence in species, however, requires more.

The goal of most consumers of taxonomic information is to simply identify species. In contrast, the aim of taxonomists is to know species: to create, test and corroborate or refute hypotheses of the distributions of characters indicative of species status; to gather as much knowledge of the attributes of species as possible, whether unique to them, or shared with related species; to describe and interpret complex morphology; to consider all relevant evidence, from fossils to morphology, ontogeny and molecular data; to understand and classify species in a phylogenetic context; and to document as much about them as possible.

Describing species is not as easy as it sounds. Characters, like species, are hypotheses and not immediately differentiated from traits that vary within a species or monophyletic group. Taxonomists have developed theories and methods for creating and testing hypotheses based on concepts of homology and apomorphy. These may seem unnecessary details to someone simply wanting to put a name on a kind of plant or animal, but it is the basis of reliable knowledge. The best that science can do is to assure that species are based on testable hypotheses, not arbitrary degrees of similarity. Absolute certainty in taxonomy, as in all science, does not exist; only corroborated hypotheses. Thus, the more evidence brought into play, the better.

Users of taxonomy can have fast, easy, and questionable identifications of species or rigorous, corroborated hypotheses of species based on all available and relevant evidence. An alarmingly widespread attitude is that identifications based on molecular estimates of species are “good enough,” but are they? Should minimalist taxonomy (see References), based on little more than a DNA barcode, be acceptable as millions of species teeter on the brink of extinction? With a mass extinction looming, we have one, and only one, chance to explore and document the diversity of species in the biosphere and the millions of species that have resulted from evolutionary history. This is a time when “good enough” isn’t nearly good enough. It is a time to insist on the best science and the most knowledge possible. After millions of species are extinct, there will be no do-overs to correct for shortcuts we now take.

Given the severity and urgency of environmental issues, were such shortcuts our only option for identifying species, we could be forgiven for accepting them. But they are not. We have it within our means to undertake a planetary-scale inventory of all species done to the highest standards of taxonomy. At the same time that taxonomy is done well, we not only make every species identifiable, we make identifications more reliable, meaningful and informative. Other than grant money, ephemeral prestige attached to using the latest technology, and going along with popular fashions, why would we ever choose to have less, and less reliable, knowledge of earth’s species rather than more?

Only by supporting taxonomists to use all relevant evidence, appropriate theories, useful technologies, and proven practices at the highest level of excellence can we provide the most reliable identifications to environmental scientists and avoid irreversible ignorance of the diversity and history of life. Environmental problems deserve to be a top priority because of the clear and present threats they represent to ecosystems and humankind. But the rapid extinction of species means that the classical mission of taxonomy is under equally great threat. We have a short period of time during which we can learn about millions of species; a fleeting opportunity to create baseline knowledge of the biosphere and preserve evidence of biodiversity and evolutionary history. This, too, deserves to be a top priority.

The inmates are running the asylum as leadership for systematics is surrendered to consumers of taxonomic information. With a primary interest in identifying species, rather than knowing them, advocates of a molecular-based approach, exemplified by “minimalist” revisions (see references), are making taxonomy more service, less fundamental science. Only when taxonomists set their own agenda, when taxonomy is pursued for its own sake, and to its own high standards, can we have both deep knowledge of earth’s species and make them identifiable. Image: scene from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 1975, United Artists, directed by Milos Forman, starring Jack Nicholson.

Users of taxonomic information focus on species because of their role in ecosystems, but evolutionary history is written in characters. This is why molecular data is not sufficient. This, and the fact that species and characters are two sides of the same coin. It is impossible to fully understand one without deep knowledge of the other. Their origins mark the same historic events, branching points in the tree of life; no character transformations, no new species. To turn to molecular data to identify species, and publish branching diagrams showing relationships among species, while ignoring the characters that make species unique and cladograms most interesting, is taxonomic malpractice. Rather than creating knowledge and applying it to the problem of species identification, a molecular-based taxonomy aims to simply document that species exist and tell them apart while learning little about them. We owe it to science and posterity to expect and demand much more from taxonomy. We should insist that taxonomy be based on hypotheses, create as much knowledge and gather as much information as possible, and expand natural history collections until such time as they fully reflect the diversity of life at and above the species level.

Supporting taxonomy done to its own high standards, exploring characters of species and clades, including complexity and emergent properties undiscoverable from DNA sequences, can assure that we learn as much as we can. Sacrificing scientific knowledge to make identifications easier is a fool’s errand because the species identified are then unconnected to corroborated hypotheses and disconnected from knowledge.

Deciding that a molecular-based taxonomy, aimed only or primarily at identifications, is unacceptable as a substitute for traditional systematics is easy if we recall why taxonomy exists: to explore, discover and know every kind of living thing, what makes each unique, and how they are related; to make sense of the complex pattern of similarities and differences among species in a phylogenetic context and classification. It is folly to undermine descriptive taxonomy and the growth and development of natural history collections, to arbitrarily favor one source of evidence because it is popular, convenient, and profitable to do so. We need to get back to basics, reject reliance on a single data source, and remind ourselves what taxonomy is and why it exists as a science. So, let’s be clear:

Taxonomy does not exist to identify species.

Species may be identified because taxonomy exists.

Unless we remember this simple truth, we will soon be left with molecular-based identifications, a planet devoid of most of its life forms, and very little knowledge. Believing that taxonomy exists to identify species gives license to cut corners, favor one data source, fail to learn as much as we can, and ignore all that has made taxonomy a scientifically and intellectually vibrant discipline. Acknowledging that we can identify species because taxonomists create knowledge of and about them is a game changer. Suddenly, we see value in all relevant evidence, in theories used by systematists, in demanding rigor not ease, in the information content of revisions and monographs, in expanding natural history collections, and in supporting taxonomy as an independent science.

Let’s assure that taxonomy, done for its own reasons, and to its own high standards, will always exist to create knowledge and, as a vitally important by-product, make species identifiable. Let’s pursue our curiosity about species, characters and evolutionary history, insisting on as much and as reliable knowledge as possible, and accepting only rigorous taxonomy as the basis for identifications. There are no shortcuts without compromises. And compromising knowledge and excellence during a mass extinction has irreversible consequences that are in no one’s best interest. As we confront the biodiversity crisis, this is no time to dumb-down taxonomy, limit ourselves to one source of evidence, or focus on simply identifying species when we could be learning volumes about earth’s species, their attributes and their history.

References

Meier R, Blaimer BB, Buenaventura E, Hartop E, von Rintelen T, Srivathsan A, Yeo D. (2022) A re-analysis of the data in Sharkey et al.'s (2021) minimalist revision reveals that BINs do not deserve names, but BOLD Systems needs a stronger commitment to open science. Cladistics 38(2):264-275. doi: 10.1111/cla.12489. Epub 2021 Sep 6. PMID: 34487362.

Sharkey, M.J., Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., Chapman, E.G., Smith, M.A., Dapkey, T., Brown, A., Ratnasingham, S., Naik, S., Manjunath, R. et al., (2021) Minimalist revision and description of 403 new species in 11 subfamilies of Costa Rican braconid parasitoid wasps, including host records for 219 species. ZooKeys 1013, 1-665. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1013.55600