Saving Systematics: Courage of Purpose

Unless taxonomists defend, explain and promote taxonomy, no one else will

After centuries of progress, taxonomy is being diluted, misdirected and deterred from its unique role among the life sciences to explore, describe, classify and understand the diversity of life, at and above the species level, at the granularity of individual characters, and in the context of evolutionary history.

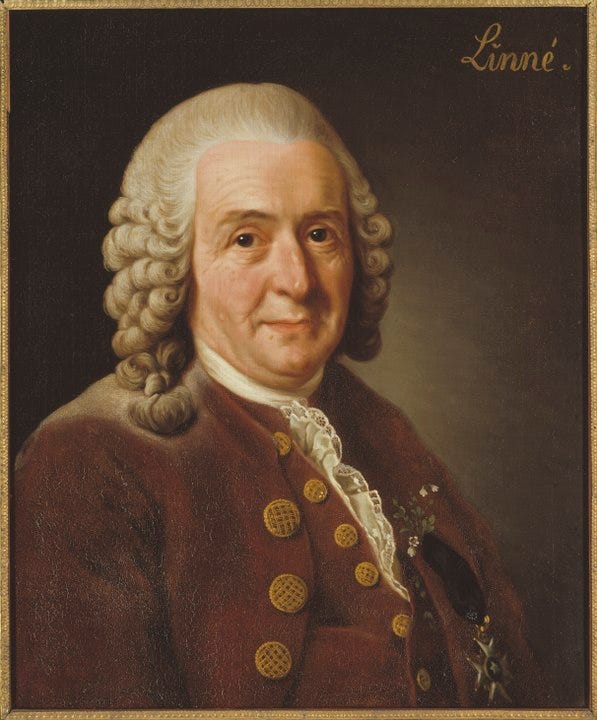

Carolus Linaeus, 1707-1778 (portrait by Alexander Roslin, 1775), whose vision of an inventory, description and classification of earth’s species has become a major challenge to science in the face of accelerated extinction.

Unless individual taxonomists, professional organizations, universities educating taxon experts, and museums and botanical gardens responsible for the growth, development, and use of natural history collections find the courage to defend, explain, and promote the priorities of taxonomy, no one else will. Ecologists are content with minimally informative DNA barcodes because they allow species to be identified. It is not their responsibility to assure that characters of species are known, or that species and clades are based on testable hypotheses rather than arbitrary genetic distances. It is not their job to care whether the mission of taxonomy is fulfilled or not, so long as obstacles to their own research are removed. I can understand this kind of self-interest, but I do not respect it. My personal interests are in taxonomy, but I support the agendas of ecology, genetics, conservation, astronomy, and others sciences because I value the growth and positive impacts of knowledge. I desperately wish to see taxonomy flourish, but by building it up on its own merits, not by undermining or trivializing other sciences for my own, narrow self-interests.

The role of taxonomy is to study and understand species, clades and characters themselves. Characters, species, clades, and the pattern of historic-evolutionary relationships among them, are the objects of taxonomic inquiry. For most biologists, little more than an identification may be immediately required. But for taxonomy and, ultimately, for human understanding we deserve to know much more. We deserve to know that which makes each species unique, the sequence of transformations by which amazingly diverse, novel and complex characters came to be, and the pattern of distribution of synapomorphies among species. Users may drill down to retrieve as much or as little information as they wish, but both science and humankind are impoverished when we fail to learn details about these aspects of biodiversity and evolutionary history. Sacrificing excellence, depth of knowledge, and range of evidence in one science to more quickly meet the needs of another is a fool’s errand, especially when we can easily have both by simply supporting taxonomy.

But having both will only happen if taxonomists find the courage to stand up against peer pressure, to push back against funding trends, to educate colleagues and the public about their unique mission, to refuse to compromise the excellence and integrity of their own discipline, to reject the superficial efficiency of focusing on only one of several informative sources of evidence, to relentlessly advocate for the growth and development of collections as a permanent record of life on earth, to defend the deep scholarship and abundant information inherent in taxonomic revisions and monographs, and to insist on scientific rigor while formulating hypotheses of characters, species and clades.

As the rate of species extinction increases, the pressure to take short cuts increases, too. For those who need only to identify species, self-serving compromises of knowledge will prove irresistible. Because earth is, for the foreseeable future, the only species-rich planet within our reach, what is at stake transcends environmental catastrophes. Stated bluntly, we have one opportunity, on one planet, to complete an inventory of life forms, create a phylogenetic classification of its inhabitants, establish a baseline of the organization of organisms in its biosphere, and preserve a record of an evolutionary history that is on the verge of being erased. Unless taxonomists have the courage to defend and pursue the vision, mission and goals of their uniquely important science, its benefits to science and humankind will be diminished or lost. Knowledge of species, characters and their history enriches our intellectual lives and allows us to understand ourselves in the context of our world and evolutionary history; it empowers ecologists, conservationists and others to access knowledge of the diverse kinds of organisms that they seek to study and save; and descriptions of characters opens a treasure-trove of models for biomimicry and solutions to problems we face or will soon face.

Taxonomy cannot survive as a fundamental, independent science unless taxonomists demonstrate an unwavering courage of purpose. Unlike experimental branches of biology, taxonomy is observational, comparative and historical, and thus misunderstood. And unlike environmental sciences, it is primarily focused on discovering what species exist, what characters they possess, and the history of transformations by which they came to be. Make no mistake, taxonomy is essential to other fields of biology. But applied knowledge, no matter how important, is most valuable when a by-product of fundamental systematics. The most, and most reliable, information is derived from taxonomy done for its own sake, not short-cuts like DNA barcodes that sacrifice deep knowledge for ease of meeting one immediate need.

If the taxonomic community finds courage of purpose, it will no longer conform to the expectations of other fields, funding trends, or fashions in science, but exert clear-eyed leadership for traditional goals that are more relevant and pressing today than ever before. Such courage will be rewarded in fantastically important ways. And, happily, a successful, independent taxonomy not only achieves its own vision for knowledge, it provides more and better information to its many user communities.

Some of the ways in which taxonomic courage of purpose should be manifested include:

· Defending the aim of systematics to discover, learn the characters of, name, and phylogenetically classify each and every kind of plant, animal and microbe.

· Accepting the responsibility of making species identifiable, analyzing their relationships, synthesizing knowledge about them, and providing a general reference system for biodiversity in the form of a phylogenetic classification, all as by-products of the pursuit of its own agenda.

· Refusing to compromise taxonomy’s prime directive to know and understand species, clades, characters, and their interrelationships. Identifying species is vitally important to biology and society, but remaining focused on species and characters themselves—not species identifications or “trees” depicting relationships divorced from characters— is the essence of systematic biology.

· Maintaining a commitment to the synthesis of all relevant evidence including, but not entirely limited to, morphology, fossils, ontogeny, and DNA sequences.

· Developing the world’s natural history collections, in aggregate and to the greatest degree possible, as a fair and full reflection of the diversity of life forms. Such collections are a primary taxonomic research resource; a physical record of biodiversity at and above the species level; and humankind’s collective memory of earth life at the dawn of the Anthropocene.

· Inspiring and educating a new generation of taxon experts to continue what has, until recently, been an unbroken chain of exploration, discovery, scholarship and science.

· Rejecting attempts to redefine taxonomy in the image of, or primarily in service to, any other science. Taxonomy should remain an indispensable partner to such sciences, but be subservient to none.

· Defending the core vision, aims, theories, and methods of systematics in the context of science and academia, while awakening in the public a deep appreciation for the majesty of the diversity and history of life.

· Integrating and adapting every useful technology while never losing sight that the goal is as much knowledge as possible, not the greatest quantity of data.

· Receiving taxonomic knowledge accumulated over centuries and accepting the responsibility to pass it on to the next generation in an expanded and improved form.

· Recognizing that we live at the interface between the Holocene and Anthropocene means that one brief opportunity exists to create baseline knowledge of the organization of the components of an incredibly complex biosphere and evidence of the results of evolutionary history on our planet. But peer pressure, greed, technology, modernism, group-think, and other factors make it increasingly challenging to reverse the decline in taxonomy. Only uncompromising conviction and courage of purpose can overcome these forces.

Peer pressure, profit motives, and serious environmental challenges are among pressures on taxonomists, and collections-based institutions, to go along with current fashions and allow themselves to be distracted from a research agenda that they alone are responsible for advancing. Were it not for the accelerated rate of extinction, taxonomists might be forgiven for allowing themselves to take their eyes off the ball. But species are going extinct at an alarming rate and while there are many sciences, organizations, and institutions engaged in environmental and conservation efforts, taxonomy stands alone shouldering the responsibility to explore, describe, and phylogenetically classify every kind of living thing on a rapidly changing planet.

Since Aristotle, it has been humankind’s destiny to understand the complex pattern of similarities and differences among living things. Since Owen, the challenge has existed to recognize homologous characters in all their guises. Since Linnaeus, the importance and benefits of completing an inventory and classification of species has been abundantly clear. Since Hennig, the value of a conceptual framework constructed around phylogenetic relationships has been apparent. And since the recognition of the biodiversity crisis, the urgency of completing an inventory of life, of preserving evidence of species in the form of museum specimens, of describing and classifying all species, has become painfully self-evident. Whether such great scientific goals are realized depends on whether taxonomists and institutions have the vision and courage to meet the unique challenges they face.