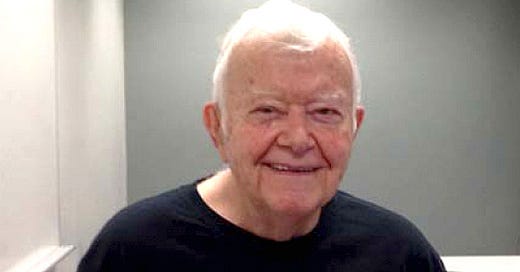

Professor Charles A. Triplehorn. T-shirt depicts the beetle Triplehornia metallica in a genus named in his honor.

This week, I focus on a taxonomist rather than a species, to honor a towering figure in entomology — and someone who had a great impact on my life and career. Dr. Charles A. Triplehorn passed away on August 25th. He would have turned 95 on his birthday next month. I first met Chuck when I was a freshman at the Ohio State University, fifty years ago this year. He was a taxonomist’s taxonomist, an ideal role model for aspiring students. Seeking his advice countless times in his office, I would find him surrounded by specimens, books, and notes, the portrait of a species explorer, museum curator, brilliant researcher, and dedicated scholar.

In the entomology community, Chuck is known as co-author of a standard textbook for college entomology students. In its most recent incarnation titled, Borror and DeLong’s An Introduction to the Study of Insects by Triplehorn and Johnson. I count myself fortunate to have come along when I did in the 1970s. I had an office adjoining Dwight DeLong’s and wonderful memories of long conversations with him. To my knowledge, I was the last student to have Don Borror serve on a graduate committee, when I pursued my Masters degree. And, of course, I had Chuck as a mentor from my arrival at OSU as a freshman all the way through to the completion of my PhD under his guidance.

Chuck was incredibly generous. He arranged for me, as an undergraduate, to be employed each summer in some capacity as an entomologist, in spite of the fact that I had few qualifications. Those experiences were important to my development, but of course Chuck knew that when he arranged them. Because of his recommendations, I sorted and identified insects for the U. S. Forest Service and the World Health Organization, and collected mosquitoes for the Ohio Department of Health. Maybe he was trying to broaden my perspective, too, given my tendency to concentrate on my projects at the exclusion of pretty much everything else. While he was a world authority on Tenebrionidae, the darkling beetles, his general knowledge — in and far beyond entomology — was truly impressive. He knew plants, reptiles, birds and mammals, as well as insects. He was the first naturalist for the Columbus Metropolitan Parks. The first curator of reptiles at the Columbus Zoo. And, he was a star member of a team that participated in weekly trivia competitions at a local bar. He would have been a shoe-in for Jeopardy.

I am not only a better entomologist for having known Chuck, I am a better person and citizen, too. To point out to me that I needed to stay informed, to be a well-rounded person as well as a scientist, he asked me during the defense of my dissertation which NFL team had never used an insignia on its helmet. I, of course, had no idea. To this day, I can tell you it is the Cleveland Browns. Point taken.

While I admired Chuck’s integrity, knowledge and accomplishments as a scientist, I was equally impressed by his humanity, memory, and irrepressible sense of humor. Working closely with him for eight years, I don’t recall a day when I did not hear at least one or two jokes. And I honestly can’t remember ever hearing the same one twice. He understood the power of humor to ease the rough edges of the human condition. Once, at an entomology meeting, he squeezed into a tightly packed hotel elevator. As the elevator ascended, Chuck broke the awkward silence, saying “You all probably wonder why I called you here.” Laughter relieved an otherwise painfully uncomfortable moment for them all. And, when Ohio State named the Charles A. Triplehorn Insect Collection in his honor, he delivered the news to me in characteristic fashion. He said, “I have always been opposed to insect collections being named after individuals… until now.”

A pivotal part of my coming of age as an entomologist was a six-week, seven-thousand-mile collecting trip around Mexico. The party consisted of Chuck, his wife and son, one other faculty member, and a group of doctoral students. I was the only undergraduate included in the expedition. I learned so much from Chuck and the advanced students, including taking my own measure against the standards they set. It gave me knowledge and confidence that would have been impossible to obtain any other way. I could do a year’s worth of podcasts with stories from that Mexico trip alone, like the time we almost pitched camp during a rain storm in a canyon prone to flash floods, or when the van of students sped past a policeman, through a stop sign, going the wrong direction on a one-way street, leaving Chuck, whose station wagon was following us, to talk his way out of a sticky situation.

But a different episode stands out as an especially meaningful moment for me. I had been on a trip to Canada and returned to realize that I had missed the deadline for applying for a faculty position at Cornell University. I was not even close to finishing my PhD, and it was two weeks past the application deadline. I asked Chuck if it was worth mailing an application so late. He said absolutely yes, and to leave the decision to Cornell whether to consider it or not. The position was that of Jack Franclement, the imminent lepidopterist, who had been Chuck’s PhD advisor at Cornell. Months later, I received a telephone call offering me the position. I raced to Chuck’s office to share the news. I will never forget the expression of genuine joy — and no doubt a good deal of surprise — on his face. I think having one of his students replace his own mentor meant as much to him as it did to me.

Too many professors think they are in the business of cloning themselves rather than awakening the potential in their students. It is common for them to assign some fragment of their own research program to a student, rather than permitting the student to find one of his or her own. Chuck had the rare ability to offer advice and guidance, to be an ever-present safety net for students, without imposing his own interests, views and practices. Perhaps he acquired this at Cornell. John Henry Comstock, who founded the entomology department there, was once asked about his philosophy for guiding students. His response was that he helped them identify a project, made sure that they had what they needed for their research, then he got the hell out of their way. There is much wisdom in giving students the basics, then the latitude to proceed in their own way, tapping their unique strengths and passion, and I always tried to do the same with my students.

It is an understatement to say that Chuck was an avid Buckeye football fan. He would plan his travel around the team’s schedule so as not to miss a home game. I sensed a strange emptiness in the horseshoe as I watched the season opener last night with one of OSU’s most loyal fans absent. The Bluffton Forever website shares accounts of a couple of Triplehorn’s claims to fame outside of science and academia, based on a reporter’s interview with him. As a six-year-old, Chuck witnessed John Dillinger’s gang rob a bank, and he saw the legendary November, 1950 Ohio State/Michigan “Snow Bowl” game. Michigan won, making both of these crime stories.

Generations of entomologists have been influenced by Triplehorn. A small, lucky number had the privilege of working closely with him. So, it is with deep sorrow and profound gratitude that I say goodbye to my teacher, mentor, friend, colleague, and role model. His was a long, richly diverse, highly accomplished life well-lived and his impacts on entomology, and countless students and colleagues, will long endure. Rest in peace my friend, and thank you for fifty years of sound counsel, inspiring example, comradery and laughter.

Further Reading

Fred Steiner (2022) Charles Triplehorn, one of Bluffton’s favorite sons. Bluffton Forever. https://www.blufftonforever.com/post/charles-triplehorn-one-of-bluffton-s-special-favorite-sons

Thomas, D. B., Smith, A.D., and R.L. Aalbu (2015) Charles A. Triplehorn: An inordinate fondness for darkling beetles. Coleopterists Bulletin 69: 1-10.

Triplehorn, C. A. and N. F. Johnson (2004) Borror and DeLong’s Introduction to the Study of Insects. 7th edition. Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove.