Decades of neglecting taxonomy is taking its toll. Nowhere on earth is every species readily identified. And in species-rich, poorly explored regions of the globe the majority of species are entirely unknown to science. So, as environmental problems increase, so too does pressure to identify species.

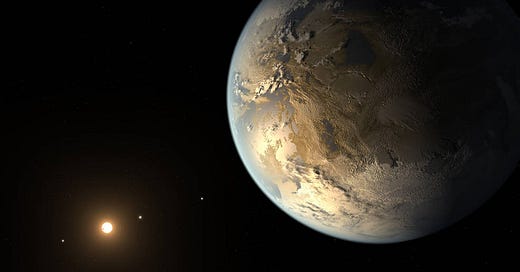

Artist's concept of Kepler-186f , the first validated Earth-size planet to orbit a distant star in the habitable zone. Image: NASA Ames/SETI Institute/JPL-Caltech.

Rather than taking commonsense steps to return support to taxonomists and natural history museums to accelerate the discovery of species, proven theories and methods are cast aside for short-cuts. One of the latest proposals is a so-called “minimalist” taxonomy consisting of a DNA barcode, a single photograph, and the least information required in order to establish a scientific name. This appears to meet the need to identify species, but such poorly described species are not corroborated hypotheses and knowing little or nothing about species themselves, what is the point of identifying them?

While there is no way to overstate the importance of identifying species, it is perhaps the least interesting aspect of taxonomy. As a fundamental science, systematics’ mission is fantastically exciting and as audacious as any other: to discover and describe every kind of living thing on, under, and above the surface of an entire planet; to explain the complex pattern of similarities and differences among them due to evolutionary history; to give species and groups of species unique names, creating the vocabulary for a rich language of biodiversity; and to synthesize all that is learned in an informative, predictive phylogenetic classification.

For the first time in centuries, taxonomy’s mission is threatened. An accelerated rate of extinction means that, in spite of heroic conservation efforts, millions of species will be lost and the time remaining to complete an inventory of species is short. Compromising excellence in taxonomy today will severely limit how much we ultimately know and understand about the diversity and history of life. Failing to achieve taxonomy’s vision will diminish our intellectual lives, limit scientific understanding, result in avoidable biodiversity loss, and reduce prospects for our the future.

We have one fleeting chance to explore and document the diversity and history of life. Missing this opportunity, or limiting our knowledge to a single data source, would be a colossal scientific miscalculation. Fortunately, by supporting systematics on its own terms, we can achieve its mission, make species identifiable, and create a wealth of knowledge about them.

There will be no second chance to explore and inventory life on earth. No other worlds on which to explore an evolutionary history so relevant to our own origins. Taking the planet Kepler 186f as an example, astronomers are discovering enticingly earthlike worlds with rocky surfaces, free water and moderate temperatures in the goldilocks zones around stars: not too close and hot, not to distant and cold, but just right to support life. But there are problems with turning to the stars to learn about biodiversity and evolution. Even traveling at the speed of light, 186,000 miles/second, it would take more than five hundred and fifty years to reach Kepler 186f and the same amount of time to return home. NASA’s Orion spacecraft has a maximum velocity of less than 6 miles/second, so the real travel time is fantastically greater. What we learn about the outcomes of billions of years of evolution, we learn here and now. Second, even if we were to reach another biologically diverse planet and complete an inventory of its species, its history would not be our own. It cannot scratch our intellectual itch to understand ourselves in the context of the world around us. And were we to inventory another world’s species, our first impulse would be to compare their diversity and history to those of earth. It would be more than a little embarrassing had we passed up the chance to explore life on our own planet.

As I argue in my forthcoming book, Species, Science and Society, we can, if we so choose, discover more species in the next few decades than in all time before or after, deepen our understanding of ourselves and the living world, create knowledge with which to conserve diverse species, and lay the foundation for a sustainable future. We can make natural history collections reflect the full range of biodiversity, enabling generations who follow to study, learn from, and marvel at the incredible diversity and improbable history of life on our planet.

But none of this is possible if taxonomy is reduced to a mere identification service. If evidence is limited to DNA. Or, if systematics departs from its centuries-old mission to discover, describe and classify species. We owe it to ourselves and posterity to support “maximal” systematics: a taxonomic renaissance that learns as much about the attributes and history of species as we possibly can with the time remaining.

Reporting from a little-known planet, somewhere in the Milky Way galaxy, this is Quentin Wheeler for the species hall of fame.

References

Sharkey, M. et al. (2021) Minimalist revision and description of 403 new species in 11 subfamilies of Costa Rican braconid parasitoid wasps, including host records for 219 species. ZooKeys 1013: 1-665.

Wheeler, Quentin (2023) Species, Science and Society: The Role of Systematic Biology. London: Routledge. 266 pp.

As a practicing taxonomist for nearly 60 years, who has described and named more than 450 species as well as numerous new genera, families and even an order or two (both living and fossil) i agree with Quentin that more resources and efforts are needed in taxonomy. And I also agree that the "minimalist" approach using only a photo and a barcode is not the way to go, not only because of a lack of additional characters and criteria for species discrimination, but also because DNA barcoding is not at this time a practical means for nontaxonomists, such as ecologists, conservation biologists and natural history survey workers to identify species, as it requires specialized and expensive laboratory equipment and time-consuming procedures. From a biological standpoint, DNA barcodes deal only with a tiny fraction of the entire genome of a species and thus are quite likely to overestimate the numbers of species in a particular taxon. Perhaps in the future, field-reading of barcodes may become possible but at present it is hard to see how this could happen. At the other end of the spectrum of taxonomic effort is the trend to integrative taxonomy, which uses all available sources of data (morphology, genetic sequences, high-powered imaging techniques, geographic distribution, etc., etc.) to discover and describe new species. This, too, is time-consuming at the source, often requires specialized and expensive equipment and significantly slows the pace of species discovery. Of course, much of the data used in integrative descriptions will not be available to those who try to use the information in the future, for whatever purpose. Somewhere in the middle are taxonomists like me who are using primarily morphological and geographical data to describe species as quickly as is consistent with good practice--that means full descriptions of important characters, comparisons with other, similar taxa, and copious illustrations using as many techniques as practicable. I think that it is important not to minimize the service aspect of taxonomy--that taxonomists provide data that is extremely useful to other researchers. After all, geneticists and molecular biologists provide data that in many cases can be used by medical researchers (for example) to advance their own work. At the same time we should continue to argue for the autonomy and integrity of taxonomy as a science in its own right. I got into taxonomy rather than another field of biology because I found it exciting and challenging. I still feel the same way after several decades of work and the publication of 250 or so taxonomic papers, monographs, book chapters and review articles. We need to find a way to more effectively transmit that excitement not only to potential taxonomists but to the general public. That this can be effective is shown by the reception of the occasional article or radio/TV attention given to new species discovery--people get excited when something new is discovered. So let's do more of this. Let's become publicity hounds for taxonomy, instead of modestly hiding our light under a bushel!