Much ado about very little

Species exploration: molecular data more utilitarian than informative

What might we learn about earth’s species, and their history, from a purely molecular approach to taxonomy? We could potentially differentiate among species and determine how they are related… and isn’t that what taxonomists do?

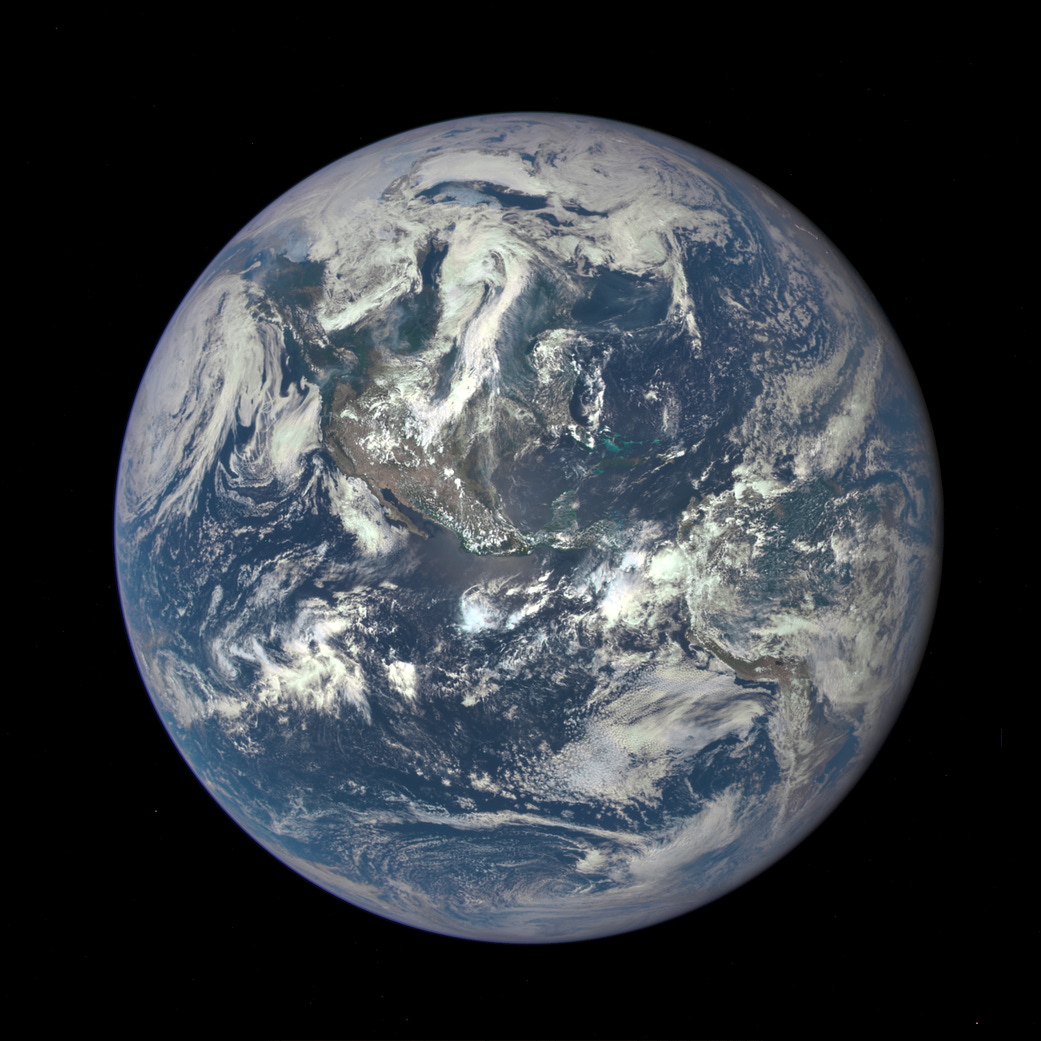

A camera on the Deep Space Climate Observatory satellite captured this view of the entire sunlit side of Earth from one million miles away (Source: NASA). Limiting taxonomy to molecular data and hoping to understand species diversity and history is like trying to learn about our planet’s geology and ecosystems with nothing more than photographs taken from afar. Remote photographs, while useful, do not reveal the whole picture. The same may be said of DNA sequences.

The answer is yes, but only in part. This would be like confining our study of Earth to information that could be gleaned from photos taken from space; being able to see the rocky planet we inhabit only from a great distance. We could recognize continents and their spatial relationships to one another, but would miss fascinating details regarding the rocks and minerals from which they are formed and the amazing story of their origins and tectonic history. A little information is preferable to complete ignorance, of course, but such pictures would be gathered to what ends? We would know little of the detailed physiography of each continent, nothing of prevailing temperatures or precipitation, of mineral deposits, of flora and fauna, and very little of ecosystems— in short, nothing much at all. Limited to molecular data, taxonomists could, at best, demonstrate that species exist, tell them apart, and determine their interrelationships. But without details, that would be a largely vacuous goal. Of some use to ecology, conservation biology, and natural resource management, yes, but falling far short of what one should expect from a serious science.

The extent to which knowledge of relationships among species—that is, a cladogram or a phylogenetic classification—is useful is directly proportionate to the amount of knowledge of the attributes of species themselves.

The extent to which knowledge of relationships among species—that is, a cladogram or a phylogenetic classification—is useful is directly proportionate to the amount of knowledge of the attributes of species themselves.The extent to which knowledge of relationships among species—that is, a cladogram or a phylogenetic classification—is useful is directly proportionate to the amount of knowledge of the attributes of species themselves. The primary value of a cladogram or cladistic classification lies in interpreting and understanding the astoundingly diverse, complex, and unexpected attributes of species. Were there no morphological diversity, example; if every species were identical in every respect except their DNA sequences, then such branching diagrams and classifications would have limited value and few applications.Cladistic classifications are powerful because they allow us to map character distributions and hypothesize evolutionary transformations; to track, in precise detail, the step-by-step history of diversification, ultimately making sense of otherwise bewildering diversity. The result of a strictly molecular approach to taxonomy—individuating species and determining their relationships—is like a jig-saw puzzle solved face-down. All the pieces are fitted together, but the interesting details, those printed on the face of the puzzle that reveal the big picture, remain unknown and out of sight. This is like a novel without a plot: we encounter protagonists and antagonists while learning nothing about them beyond their names and the fact that they exist. Such an intellectually impoverished taxonomy might be kept around for its utilitarian value to other biologists, but it would cease to advance deeply meaningful knowledge of life on earth; cease to be worthy of its traditions, many achievements, and long history.

Taxonomy cannot be pursued only or primarily as a service to environmental sciences and remain a rigorous or independent science.

Taxonomy cannot be pursued only or primarily as a service to environmental sciences and remain a rigorous or independent science.Taxonomy cannot be pursued only or primarily as a service to environmental sciences and remain a rigorous or independent science. Its aims fundamentally differ from those of experimental and environmental biology. Its mission is not simply to discover and make identifiable species: it is to know species, as individual kinds, at the granularity of the characters that make them unique, and the synapomorphies they share with others. Distinguishing among and knowing species are two very different goals. Molecular data has value for both, but pursued in the absence of evidence from morphology and fossils it is more useful for the former than the latter.

A cladogram or phylogenetic classification is the key required to unlock the amazing, improbable story of billions of years of evolutionary history. Without comparative, descriptive taxonomy, no detailed story may be told. Without attention to morphology, cladograms are naked stick figures with almost nothing to explain beyond relationships among names at their terminals. Epithets that, without descriptive taxonomy, tell us no more about the species they represent than names in a telephone directory tell us about individual human beings.Molecular data is a relatively new, powerful tool that, like every tool, excels at some things and is poorly fitted to others. Augmenting morphology, fossils, and ontogeny, DNA data becomes a valuable tool with which to explore and understand biodiversity at and above the species level. But pursued in the absence of knowledge drawn from other sources, the greatest potential in DNA data will never be realized. In the absence of knowledge of the detailed attributes of species and clades, a DNA-based taxonomy will devolve into a pedantic exercise of minimal value, one incapable of achieving the grand vision of taxonomy to explore, know and understand species and their unique, often complex and unanticipated, characters and history.Without collections of whole specimens, without detailed descriptions of morphology, dependent on DNA data alone, taxonomy becomes as boring and purely utilitarian as many experimental biologists, ignorant of its theories and practices, have long and wrongly accused it of being.There is far more at stake in the current struggle between molecular and traditional approaches to taxonomy than jobs, prestige and grant money. Because of accelerated rates of extinction, we have one rapidly disappearing opportunity to explore, discover, document, and make known the kinds of life forms inhabiting our planet. One chance to study and describe them. One opportunity to make natural history museums a permanent record of biodiversity, before the sixth extinction is complete. One chance to fill in details of evolutionary history before they are erased. One opportunity to preserve evidence of our relatives, near and distant, from which we can learn about the origins of the attributes that make us human. One chance to thoroughly explore the diversity and history of life on what is possibly the only species-rich planet on which we ever set foot. That is a lot to sacrifice in order to be popular among colleagues; a lot to sacrifice for short term success in grantsmanship; a lot to sacrifice to appear modern, trendy, and technologically savvy; a lot to sacrifice to court the approval of experimental biologists; a lot to sacrifice for natural history museums making a Faustian bargain for ephemeral popularity and funding at the price of an inventory of species on a rapidly changing planet.DNA data, and so-called minimal taxonomy, are creating an index to a book that may remain unwritten. Because descriptive, comparative, revisionary taxonomic studies are ignored, because natural history museums have lost the plot, most pages of that book may be forever blank. It would seem to matter little how complete or accurate the index is when it leads us to no more detailed or interesting knowledge than a list of names and a database of DNA sequences.

I do not for a minute minimize the importance of making species identifiable in order to advance conservation and environmental goals; these are noble causes that taxonomists are committed to supporting. But that support need not cause the death of taxonomy as an independent science. By pursuing taxonomy on its own terms, we can have both fundamental knowledge of species, characters and history and the information desperately needed to confront environmental issues. Moreover, when taxonomy is done on its own terms, the reliability and information content of taxonomy is far greater, making it even more valuable for environmental goals.

The traditions and questions of taxonomy have been honed over centuries through deep thought, debate, and trial and error, and are both timeless and fundamental to understanding of the living world. Our cynical fascination with the latest technology blinds us to the depth of understanding possible if we stay the course, building on centuries of advances rather than starting over. The urgency of mass extinction is causing the community to focus on immediate needs in a way that unnecessarily compromises longer term, and in certain ways even more important, goals for taxonomic knowledge. It is time to pause and ask what we wish to ultimately know about living things and their history, before it is too late to learn them.

Taxonomy must provide strong, reliable support to conservation and environmental sciences, of course, because our lives and well-being depend on it, and because deep understanding of ecology and ecosystems are fascinating, too. But we must, at the same time, pursue the traditional goals of taxonomy because they uniquely fulfill an irrepressible urge of the human spirit to explore and understand the diversity of life around us. Environmental goals are urgent and necessary, but we are capable of aspiring to things beyond our physical survival. Taxonomy addresses our innate curiosity about, and desire to comprehend, self, biodiversity, and world. The traditions of taxonomy are exciting, intellectually fulfilling, and enrich our lives in countless ways.

We must ignore Sirens luring us into the rocky shoals of a molecular-based taxonomy. Molecular taxonomy pursued in isolation is, in the end, much ado about, if not nothing, then very little. Let’s embrace instead the scientific vision, theories and methods of traditional taxonomy that will steer us into deeper waters rich in knowledge and understanding. We owe it to ourselves, and future generations, to explore and preserve evidence of as many species as possible; to lay a multi-dimensional foundation for taxonomy that will make evidence of species, characters and history most accessible, impactful, and understood; and to rise to the challenge of a comprehensive inventory and description of earth’s life forms before the toll of mass extinction is paid in full.