Insecta: Phasmatodea: Phylliidae

Vaabonbonphyllium rafidahae

There are about fifty species in the family Phylliidae, the leaf insects. As the name suggests, these insects are noted for their general appearance that looks very much like a leaf. More or less flattened, frequently green or brown, often with leaf like lobes on their body and/or legs, they visually blend into the vegetation on which they stand and feed. Leaf insects are distributed from islands in the Indian Ocean to South Asia, Southeast Asia, Papua New Guinea, and Australia in the western Pacific. Melanesia — encompassing New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, New Caledonia, and nearby islands — is strikingly diverse for leaf insects. Even more, studies suggest that Melanesia may be the ancestral source for all phylliids.

Leaf insects are from one to four inches in length. When males are not present, females may reproduce parthenogenetically. And when they lay eggs, they fling or drop them to the ground. Young nymphs hatch, then climb vegetation. Their family tree, no pun intended, is currently being reevaluated in light of recently discovered species, re-analyzed morphology, and a growing database of molecular sequences. The earliest fossil of a leaf insect dates to about 47 million years ago.

In 1519, the Venetian scholar and explorer Antonio Pigafetta joined Ferdinand Magellan on his famous expedition to the Spice Islands and, following Magellan’s death in the Philippines, was one of only 18 men to complete the entire circumnavigation. In his diary, he records what is thought to be the first reference to a leaf insect by a European. He commented that, on Cimbonbon Island, there are certain trees, the leaves of which, when they fall, are animated and walk about. Clearly, he was mistaken about what he had seen. But without closer inspection, he can be forgiven for being fooled by such elaborate camouflage.

Photos of living leaf insects. (A) male Rakaphyllium schultzei, Wokam Island, Aru Islands, Indonesia, by Loic Degen (Switzerland); (B) brown form of female Acentetaphyllium brevipenne (Alamy stock photo “rainforest of New Guinea". Source: Cumming & Le Tirant (2022), by permission.

Richard Dawkins once described evolution as improbability on a colossal scale. His words certainly apply to leaf insects, or walking leaves as they are sometimes called… and not just in Pigafetta’s colorful report. These insects mimic leaves in astonishing detail: shape, size, color, what appear to be the midrib and veins of a leaf, and even dark spots that resemble diseased leaves and irregular margins appearing to be a leaf with a bite taken out of its edge, all play into phylliid camouflage. Were that not enough, even their behavior can be leaflike, whether sitting still among real leaves on a branch or while moving about. When they walk, they may sway in a manner reminiscent of a leaf in a breeze. Leaf insects are strongly sexually dimorphic and it can be difficult to confidently match up males and females of the same species. Males are smaller and fly. Females are larger and relatively stationary, spending their lives in the forest canopy. The same camouflage that makes them so impressive, giving them a good measure of protection from predators, also hides them from the gaze of insect collectors, making many species very rare in museum collections.

A new genus was recently described from the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea with a name that is a mouthful: Vaabonbonphyllium. The name is derived from a phrase in the Teop language meaning “wait for the night to come,” combined with “phyllium,” a Latinized form of the Greek word for leaf. Motionless by day, these insects venture out after dark. Perhaps not surprisingly, for this reason they are rarely collected and little is known about them.

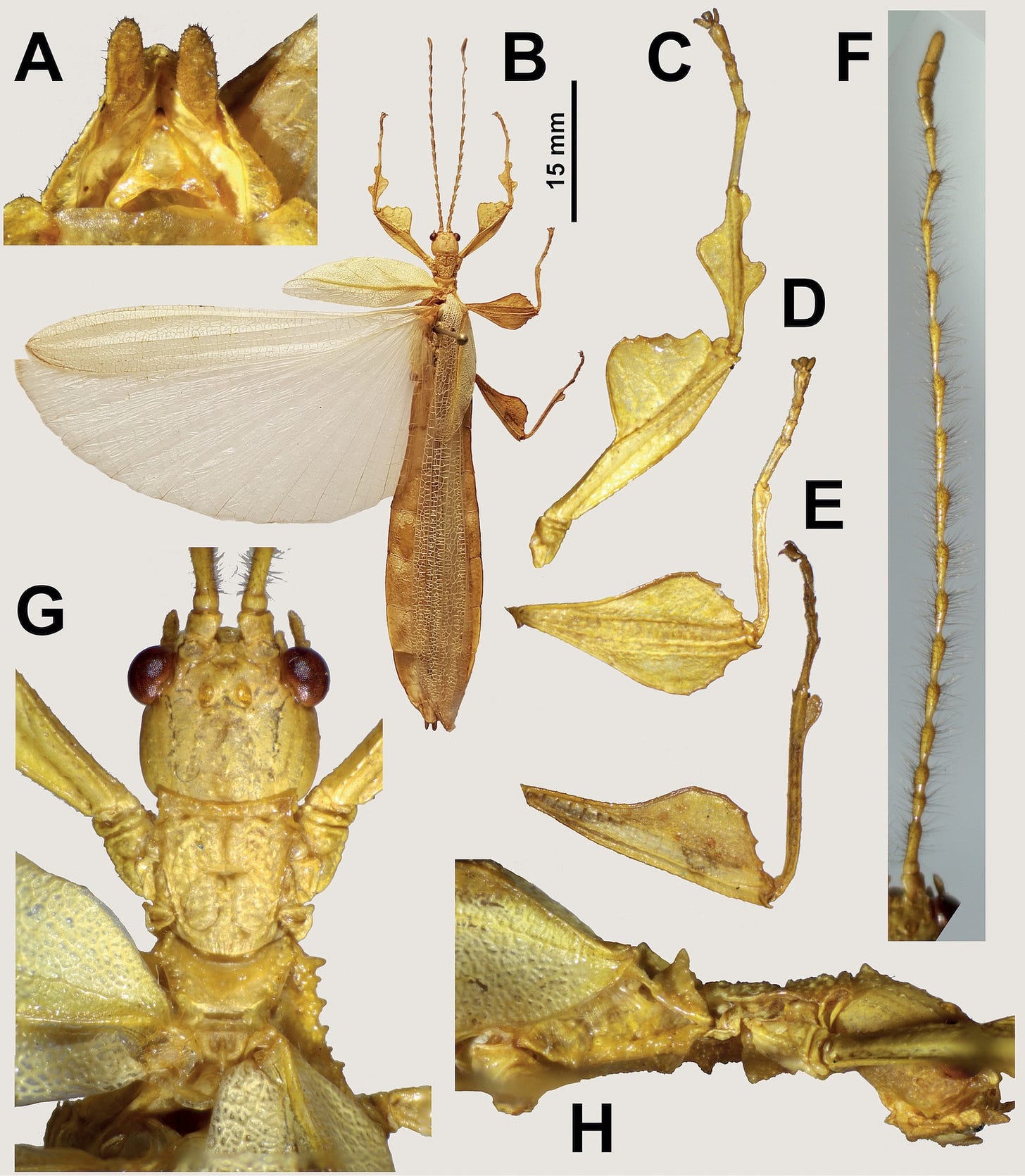

A new species in the genus is Vaabonbonphyllium rafidahae. This species is, so far, known from a single specimen collected at Mount Hagen, Western Highlands Province, Papua New Guinea. The preserved specimen has faded to yellow, but was green in life. It is about 53 mm, or a little over two inches, in length. The specific epithet is a patronym honoring Rafidah Munsey who, with her husband Larry, have lived in Borneo for the past seventeen years studying the diverse fauna of longhorn beetles.

Only known specimen of new species Vaabonbonphyllium rafidahae: (A) genitalia, ventral; (B) habitus, dorsal; (C) protibial and profemoral lobes; (D) mesotibial and mesofemoral lobes; (E) metatibial and metafemoral lobes; (F) antenna, dorsal; (G) head and thorax, dorsal; (H) head and thorax, lateral. Photos by Royce T. Cumming. Scale bar applies to photo B only. Source: Cumming & Le Tirant (2022), by permission.

Naming new species based on single specimens is sometimes frowned upon in taxonomic circles, the preference being to wait until a sufficient number of specimens have been collected to assess variation. But in practice, the wisdom of this view depends. In some groups, with species showing only slight differences and high variability, it could verge on taxonomic malpractice to name singletons. But in many other cases, including this one, a species is so different from any of its relatives, so obviously unique, that there really is no reason to wait to make its existence known. Details setting this new leaf insect apart from close relatives — let’s save time and call it V. rafidahae, shall we? — include abdominal segments of relatively equal width, lobes on the femora of the front legs that are wider than the femoral shaft, and interior and exterior lobes on the middle legs of approximately equal width. Such conspicuous attributes, especially in the hands of a knowledgeable expert, is more than enough evidence to justify hypothesizing species status. And, making the species known encourages additional collecting and observations.

The appeal of having a leaf insect as a pet is obvious, and about a dozen species have been commercially sold on the market. Given what is happening to their habitats, and our inadequate knowledge of their population status and natural history, caution should be exercised to avoid over-collecting them for amusement. If you find yourself in Melanesia and think you’ve seen cavorting foliage, step away from your mai tai and don’t be a Pigafetta — leave it to the experts.