Dewey, or don't we?

Do we re-embrace taxonomy's grand vision to explore the diversity and history of life, or do we resign to permanent ignorance, using DNA to identify species about which almost nothing is known?

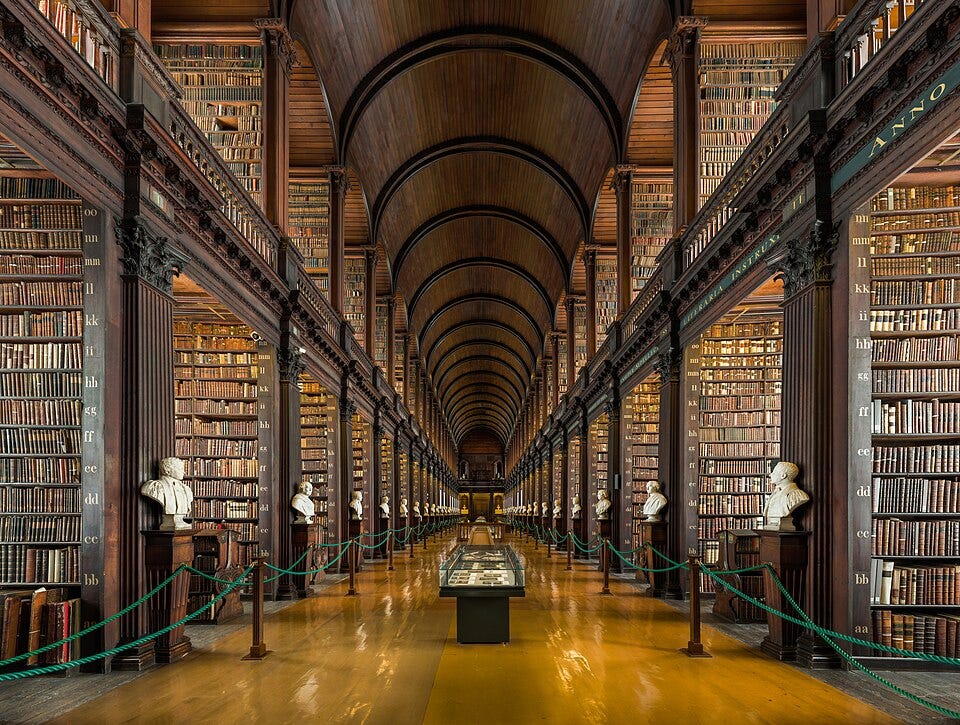

The Long Room, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland. Credit: Diliff, 21 July 2015, CC-BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikipedia.org

Just as the Dewey decimal system allows one book to be recognized among many, DNA barcodes make it possible to identify species. However, if we never read books—or, in the case of species, if we never study, describe and understand their characters—what is the point? Unless you read the book, does it matter whether it is Brave New World or A Tale of Two Cities? For similar reasons, identifying species means little if characters are unknown. Names, or DNA barcodes, tell us no more about species than entries in a telephone directory tell us about the persons listed. To the extent that DNA barcodes are informative and useful, it is because they facilitate access to knowledge, much of which is created by taxonomists.

To me, it is inconceivable to love knowledge and not have deep affection for libraries. When I visited Trinity College, in Dublin, I was awestruck. The Long Room is, for lack of a better description, scholarship made tangible. Given a daily ration of food and Guinness, any scholar would be tempted to remain there, living out their days immersed in that architectural manifestation of knowledge.

In high school, I worked evenings in a public library where I learned respect for the organizational efficiency of the Dewey decimal system. Later, as a student at The Ohio State University, Dewey’s system guided me to my favorite study site: a small desk secluded among the stacks of the Botany & Zoology Library. I found that being surrounded by books close to my interests was inspirational, with an added benefit. During breaks from my studies, I explored books I might otherwise never have encountered.

While the proximate value of the Dewey decimal system is to locate and recognize books, its ultimate power is much greater: it leads us to knowledge. Simply identifying books, whether recognized by title or decimal number, leaves us as ignorant as we began. To gain knowledge from books, we must read them—and, to learn about and from species, we must study their characters. Preference for a molecular-based taxonomy, focused on identifying species about which little or nothing is known, requires an astonishing lack of curiosity. Only by exploring characters—frequently novel, complex, and entirely unexpected—do we discover that which makes species, and evolutionary history, most interesting and worth knowing.

There are legitimate, purely practical reasons to identify species, of course, in agriculture, medicine, commerce, ecological research, and many other pursuits, and this is where molecular data has the potential to shine as an identification tool. Such identifications, however, should not be confused with the mission of taxonomy as a science. They are a fringe benefit, an application of knowledge, that does not reflect taxonomy’s intellectual breadth and depth, or its ultimate importance to science and humankind. It is important to recognize that, divorced from more informative evidence—isolated from studies of morphology, fossils, and ontogeny—DNA barcodes are of no more use than a card catalogue in a library whose books are never read.

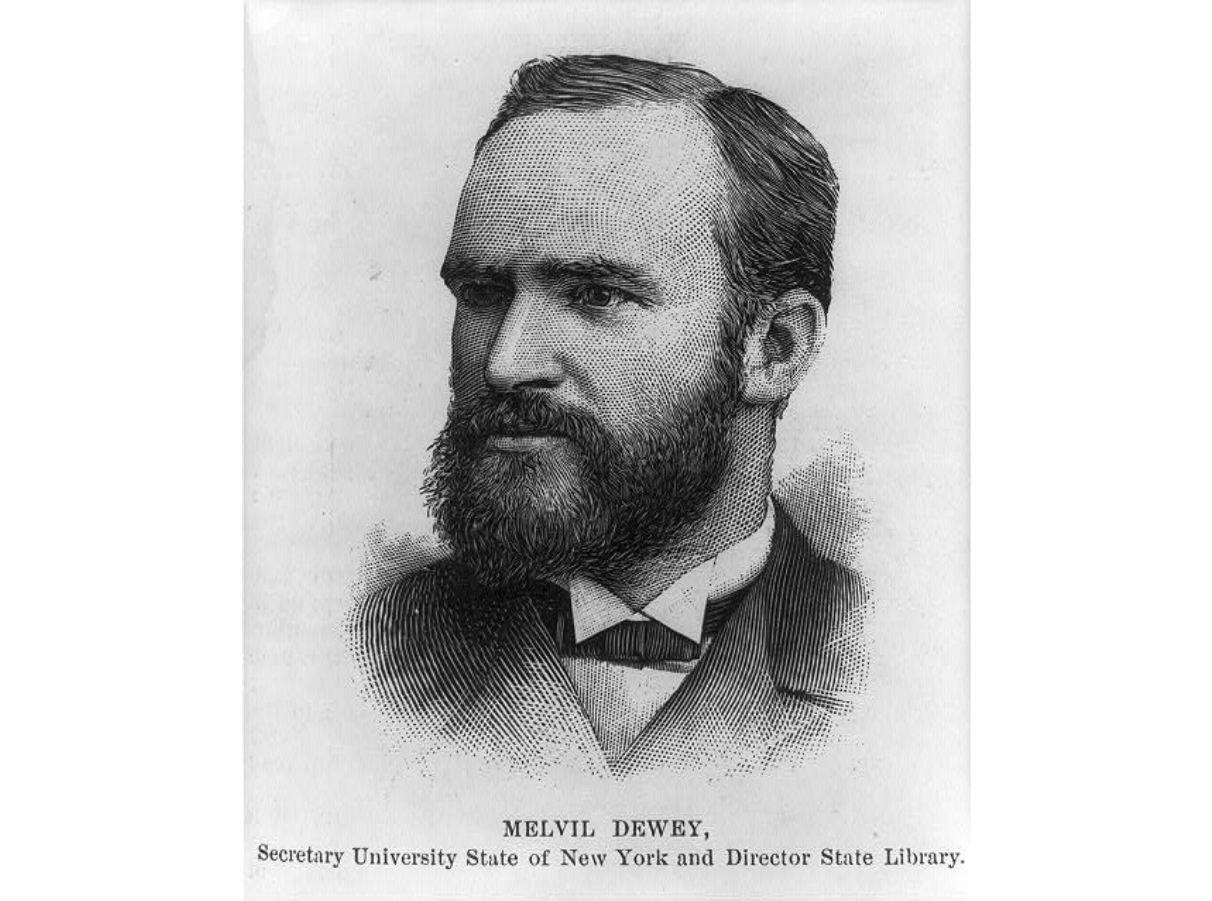

Melville Louis Kossuth Dewey (1851-1931). While I admire the usefulness of “Melvil” Dewey’s decimal system, the repugnancy of his racist, antisemitic, and sexist views has not diminished with time. An example—one among many, and far from the worst—was his requirement that women applicants to the School of Library Economy at Columbia College provide a photograph because, in his words, “you cannot polish a pumpkin” (J. Kendall, 2014, “Melvil Dewey: Compulsive Innovator,” American Libraries Magazine, March 24). Image: Wood engraving published in Harper’s Weekly, vol. 40, 1896. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division; digital ID: cph 3a40527 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a40527

Simply identifying books, recognizing them by title or decimal number, leaves us as ignorant as we began. To gain knowledge from books, we must read them; to learn about and from species, we must study their characters… It is important to recognize that, divorced from more informative evidence—isolated from studies of morphology, fossils, and ontogeny—DNA barcodes are of no more use than a card catalogue in a library whose books are never read.

I appreciate the need for, and importance of, identifications, and I’m delighted that taxonomy makes them possible. But, when taxonomists abandon the goals of their own science, when they focus on providing identification services rather than pursuing knowledge, their actions become antithetical to science and limit what and how much we learn about earth’s species and their history. In contrast, when taxonomy is practiced at its highest levels of excellence, when it is driven by curiosity to pursue all promising evidence, users of its information may have greater confidence in the reliability of identifications and benefit from access to an abundance of knowledge. It is understandable that casual users of taxonomic information, and non-taxonomists in general, may have little or no interest in the theories and methods used to arrive at an identification. They should, however, be concerned whether taxonomy has been done well, and whether species are based on testable hypotheses or an arbitrary measure of genetic similarity. A scientific name—an identification—looks just as convincing whether it was corroborated by careful observations and multiple sources of evidence, or hastily arrived at with with a bare minimum of information.

A scientific name—an identification—looks just as convincing whether it was corroborated by careful observations and multiple sources of evidence, or hastily arrived at with a bare minimum of information.

Brendan Gleeson (left; as Sheriff Hank Keough) and Oliver Platt (right; as Hector Cyr) in the 1999 comedy-horror movie Lake Placid. Directed by Stephen C. Miner; produced by Fox 2000 Pictures, Phoenix Pictures, Rocking Chair Productions, and Stan Winston Studios; distributed by 20th Century Fox.

In the 1999 movie Lake Placid, Sheriff Keough says that he has never heard of a crocodile crossing an ocean, to which the crocodile expert, Hector, sarcastically responds: “Well, they conceal information like that in books.” It is possible to identify a species with DNA and still know little or nothing about it. And, as “minimalist” taxonomists have demonstrated, it is even possible to name new species knowing equally little about them. For those digging no deeper than DNA sequence data, most knowledge about species, if it exists, remains concealed in taxonomic descriptions, revisions and monographs; and rich deposits of additional knowledge, derivable from specimens in natural history collections, remain un-mined. By whatever means a species is identified, it is taxonomy that creates and compiles knowledge of morphology, geography and natural history and makes it retrievable with phylogenetic classifications and scientific names. Without so-called descriptive or revisionary taxonomy, an identification tells us almost nothing of interest beyond a name.

For those digging no deeper than DNA sequence data, most knowledge about species, if it exists, remains concealed in taxonomic descriptions, revisions and monographs; and rich deposits of additional knowledge, derivable from specimens in natural history collections, remain un-mined.

Because the majority of species are undiscovered, undescribed and unknown to science, because most descriptions are far from complete, and because predicted distributions of characters must be tested repeatedly, taxonomy’s descriptive work has only begun. Add to this an alarming increase in the rate of extinction and there could be no worse time to limit what we learn about species to molecular data. Stated plainly, our ignorance of characters is little improved by molecular data unless it is integrated with knowledge of morphology, ontogeny, and the fossil record. It is true that, by placing a species in a higher taxon purported to be monophyletic, such as a genus or family, we may provisionally predict that it shares certain documented synapomorphies; but this assumption, as well as the unique combination of characters that distinguish it as a species, must be confirmed by observation.

Not every user of taxonomic information wants or needs to know more characters of species or clades than the minimum required for an identification. There are reasons to simply identity species, very good ones. And a DNA barcode, or, in many cases, a few morphological features, may be sufficient for that purpose. Conservation biologists want to recognize species they hope to save; farmers want to detect the arrival of crop pests; and, ecologists deserve the option of drilling down to species-level interactions, if or when they choose to do so. Because species may be identified with a DNA barcode does not, however, justify ignoring other, more complex, evolutionarily novel, and interesting characters. Nor does it justify shortcuts that replace knowledge and hypotheses with rote procedures and arbitrary thresholds of similarity. Identifications are most reliable when they take into account as much evidence as possible; and they are most informative when species have been carefully studied, compared and described. To intentionally restrict taxonomy to molecular data is beyond wrongheaded; it is scientific malpractice unnecessarily limiting the growth of knowledge. Both taxonomists and users of taxonomic information are best served when taxonomy is done to high standards of excellence, and when as much relevant evidence as possible is considered.

To intentionally restrict taxonomy to molecular data is beyond wrongheaded; it is scientific malpractice unnecessarily limiting the growth of knowledge.

We are free to read books or allow the knowledge they contain to remain concealed from us, just as we are free to learn as much about species as possible or simply identify them with DNA. In taxonomy, ignorance is a choice, not an irreparable condition. It would be a mistake to ignore the numerous uses for DNA data—but a much greater one to neglect other, more information-rich sources of evidence.

Because of accelerating rates of extinction, taxonomy is at a tipping point. With little time to explore, discover, describe, name and classify earth’s species, we must do it as thoroughly as possible the first time. There is little margin for error… and no excuse for shortcuts. We shall have no second chance to inventory life on earth or preserve evidence of species, characters and evolutionary history. The discovery of imperfectly preserved fossils make headlines when their characters bridge gaps in the evolutionary record. At the same time, we diddle with DNA as thousands of species, many no less remarkable, interesting, or evolutionarily significant in their own ways, join the ranks of the extinct, making no effort to preserve specimens for science and posterity.

We can do taxonomy well, create a priceless legacy of knowledge, and expand and develop natural history museums as a permanent record of species diversity; or, we can continue the trend toward a molecular-based identification service, imposing tragic, irreversible ignorance of species, characters and evolutionary history on future generations. We must decide which, and we must decide now. Doing taxonomy well takes molecular data into account. But molecular-based taxonomy, as currently practiced, intentionally neglects other, in important ways more informative, sources of evidence.

Our choice is clear. We can continue along the easily funded, popular, molecular-based path, focus on identifying species, and enjoying short-term praise and profits. Or, we can resolve to overcome the daunting challenges of taxonomic excellence; to complete a comprehensive, planetary-scale inventory of species; to return the focus of natural history museums to collections-based research, differentiating and elevating them in importance; to describe, analyze and understand the origins of the characters of species and clades; to make classifications phylogenetic and informed by as much evidence as possible; and, to create a legacy of detailed, scientifically impactful, and intellectually enriching knowledge of immediate and enduring value.

For those padding their Curriculum vitae, seeking easy grant money, desperate for approval from experiment biologists, or willing to reduce a noble science to a mere identification service, the enticements of the former may prove irresistible. But, for anyone who values knowledge, is curious about the diversity and history of life, or who truly understands the significance of taxonomy to science and humankind, there is only one acceptable choice.

Instead of following fads and seeking the approval of colleagues who neither understand nor respect taxonomy’s history, theories, methods or mission, it is time for taxonomists to lead, advancing their science, in spite of daunting bio-political headwinds, into an era of unprecedented excellence, discoveries and advances. Taxonomists must defend, and advocate for, the uniquely important mission of their science for the simple reason that no one else will. They must explore and document the diversity of species, describe and analyze all relevant characters, refine phylogenetic classifications, and grow and develop natural history collections as a permanent record of species diversity and the history of life. And they must do so while, at the same time, enabling identifications and defeating the forces of ignorance, self-interest and malice responsible for the neglect of their science.