Collecting, Compassion and Knowledge

Collecting museum specimens is more important now than ever—and represents a special kind of compassion that informs biodiversity conservation and respects every species with acknowledgment

The veins in my forehead nearly popped as Allison Byrne described a future for natural history museums with few newly collected specimens beyond road-kills. Instead, she envisions DNA samples, photographs, and observations of species combined with extended uses for existing collections. Not surprisingly, she is not a systematist and, conveniently, her research does not depend on collections that are sufficiently representative to allow us to study, compare and thereby understand all species, learn their characters, and analyze their relationships with morphological evidence. She seems unaware of the reason that that taxonomists assemble collections and their highest use in scientific research. She describes herself as “a disease ecologist and conservation biologist specializing in using genetic and genomic techniques to study amphibians and the pathogenic chytrid fungus,” and she adds that she is “passionate about conservation, mentorship, community, animal ethics, and frogs (not necessarily in that order).”

Considering what is happening to amphibian populations, going extinct thousands of times faster than in prehistory, it is appropriate to have a heightened awareness of the impact of collecting specimens of frogs today. Random or excessive collecting raises serious ethical questions. But these are not the only ethical questions facing science and natural history museums. There are compelling scientific reasons to continue to collect whole specimens, even for amphibians. Of course, this should be done thoughtfully, sparingly and purposefully when populations are vulnerable to extinction. But it is a false narrative to claim moral high ground by banning the collection of specimens or to claim that remaining ignorant of species is compassionate, especially during a mass extinction.

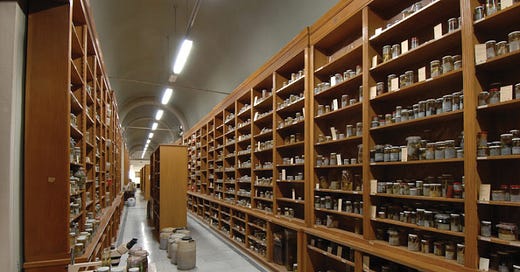

The herpetology gallery, Museo di Storia Naturale, University of Florence. Photo: S. Bambi. Source: Andreone F, Bartolozzi L, Boano G, Boero F, Bologna M, Bon M, Bressi N, Capula M, Casale A, Casiraghi M, Chiozzi G, Delfino M, Doria G, Durante A, Ferrari M, Gippoliti S, Lanzinger M, Latella L, Maio N, Marangoni C, Mazzotti S, Minelli A, Muscio G, Nicolosi P, Pievani T, Razzetti E, Sabella G, Valle M, Vomero V, Zilli A (2014) Italian natural history museums on the verge of collapse? ZooKeys 456: 139-146. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.456.8862

Like many molecular geneticists and experimental biologists, Byrne seems quite happy to constrain the growth of knowledge in systematic biology so long as her own research interests remain possible. On more than one occasion I have heard experimental biologists question why we should waste time describing and naming new species that will soon be extinct; after all, they selfishly reason, they will not be available for experimentation, so who cares whether they are known and named? Such intellectual myopia might be forgivable for a person on the street, but knowingly arguing for ignorance over knowledge by a scientist is to me shocking. I am not personally drawn to nor especially interested in molecular genetics, and I certainly have no close association with astronomy, yet I strongly support research that deepens our understanding of life and the Universe.

Tree-hugging is meant to be a metaphor, not a prescription for field work. There is a distinction between conserving a single threatened species, like the Panamanian variable harlequin frog Atelopus varius, and conserving biodiversity—and only the latter holds the best chances for self-perpetuating ecosystems and a diverse biosphere. Conservation need not impose ignorance of biodiversity in order to save it; in fact, the truth of the matter is just the opposite. The more we know and understand the diversity of, and relationships among, species, the better positioned we are in to develop measurable and successful biodiversity conservation strategies. Writ large, this includes E. O. Wilson’s Half-Earth concept of global conservation which would set 50% of the surface of our planet aside to biodiversity in order to save 85% of species; but its success depends on knowing which bits of geography to cede to biodiversity and that, in turn, depends on knowing what species exist and where they live.

If, as in the best traditions of systematics, species are to remain explicitly testable hypotheses rather than arbitrary degrees of genetic similarity, then continuing to collect whole specimens and expand natural history collections is critically important. Further, if we wish to understand the origins of biodiversity and details of evolutionary history, then such collections are necessary. Many undescribed species exist among current museum backlogs, but they represent only a small fraction of unknown species. Perhaps 80% of plant and animal species remain unknown to science, unrepresented in museum collections. We have made strides in understanding evolutionary processes, from mutations to natural selection, but we have only begun to tell the actual story of evolution at and above the species level as it happened. Without collections this story will never be told. Fascinating details of that story are written in morphology that can only be studied, interpreted, and understood with access to specimens in museums.

The least that we can do to honor other species is to dignify them with a name and recognition of what makes them unique. There is no compassion in allowing millions of species to go extinct entirely unknown; it diminishes our scientific understanding and it is as callous and indifferent as the actions with which our civilization has driven species to the brink of extinction. We have no reason to believe that we will, for the foreseeable future, find another planet that is as biologically diverse as earth. We have one and only one opportunity to explore and gather evidence of species diversity and evolutionary history. Imposing ignorance on all future generations isn’t compassionate; limiting conservation to good intentions when we could have knowledge of species isn’t compassionate; and selfishly attending to the needs of experimental biology while ignoring the fundamental requirements of systematic biology isn’t compassionate, either.

Acting on feelings rather than logic, acting on self-interest rather than scientific opportunity, it sounds superficially compassionate to stop collecting specimens and limit ourselves to DNA samples and photographs. But this leads to ignorance that should be unacceptable on a planet undergoing radical change. Knowledge is key to a brighter future that includes biodiversity conserved, evolution understood, and a respectful relationship between humans and other species. No one wants to impose suffering on animals or hasten extinction. Taxon experts who devote their life to exploring and understanding the species of a group of plants or animals have a deeper love and concern for them than anyone else, and to characterize their collecting as uncompassionate reveals a serious misunderstanding of systematic biology, how its hypotheses are formed and tested, and how its knowledge advances.

With thousands of extinctions each year, including huge numbers of species unrepresented in natural history museums, this so-called compassionate collecting is precisely the wrong approach. We need to collect specimens like there is no tomorrow, because for millions of species this may literally be the case. This does not mean indiscriminate, excessive, or cruel collecting. It means scientifically informed, thoughtful collecting, appropriately judicious when called for, that is our last defense against profound ignorance of species diversity and history. Just as we are driven to understand the origins and history of the Universe, we harbor a deep curiosity to know also the source and history of the biodiversity of which we are part. Taxonomy done well, a species competently described, requires the collection of whole specimens that may be studied in detail and reexamined in the future. Testing the distribution of attributes, status of species hypotheses, and phylogenetic relationships— discovering many of the most improbable and fascinating outcomes of evolution — means detailed comparative morphology, not just DNA sequencing. And that is only possible given access to museum collections that are sufficiently representative of species diversity.

So-called compassionate collection makes for a nice bumper sticker but is a recipe for profound ignorance about species diversity and evolutionary history. Collecting by taxonomists serves high scientific, intellectual, and practical purposes and is responsible, being informed by deep knowledge of and concern for the taxa involved. It is a necessity for systematic biology in order to know earth’s species and the story of the origins of their diverse attributes. The level of ignorance of most species, imposed by no longer collecting museum specimens, would be profound, would likely result in a lower level of biodiversity conserved, and would forever preclude a detailed understanding of evolutionary history on the only biologically diverse planet within our reach. I see little compassion in allowing species to go extinct unknown; in making poorly informed conservation priorities; in allowing clues for biomimetic solutions found among species to simply disappear; or in remaining ignorant of the story of life on a planet undergoing an extinction crisis. Stupid is as stupid does. We owe it to the diversity of life on earth, to the prospects for future evolution, and for the growth of human understanding to collect specimens while the opportunity exists to do so. This doesn’t mean being irresponsible or carelessly mass collecting from vulnerable populations, but it does mean recognizing that we deserve to know more about species and evolution than DNA and photographs can tell us.

For scientific understanding, conservation, and the hope of creating a sustainable future it is imperative that we continue to grow and develop natural history museums such that they reflect, as fully as possible, the number and diversity of species on our planet. It is in conserving whole specimens that we express true compassion for other species, their future, and their unique contribution to the diversity and story of life. It is disingenuous to claim to care about species when we cannot be bothered to give them names, find out what makes them unique, or preserve specimens as evidence that they existed. Systematists don’t tell geneticists and experimental biologists what evidence they need in order to do their research. It takes a special kind of selfish narrow-mindedness, and an alarming lack of understanding, curiosity and compassion, to impose permanent ignorance on an entire field of science.

Further Reading

Byrne, Allison Q. website [https://www.alliebyrne.com/]

Wheeler, Q. (2023) Species, Science and Society: The Role of Systematic Biology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Wilson, E. O. (2016) Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. New York: Liveright.