A Red List of Taxonomic Ignorance

Systematists should compile and periodically update a 'red list' of gaps, large and small, in the extent and quality of knowledge of Earth's species

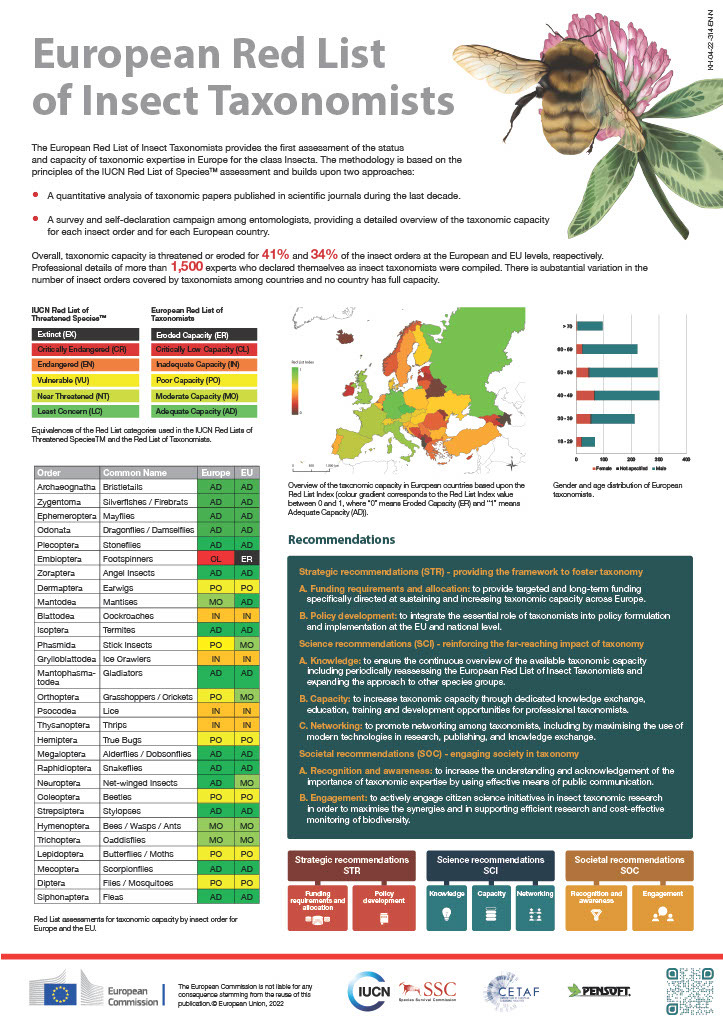

Like so many EU documents, the 2022 publication European Red List of Insect Taxonomists (a poster summary of which is shown, below)—a sobering snapshot of the state of taxonomic expertise across Europe—has so far had modest impact. As the biodiversity crisis heats up, however, the importance of investing in continued, and expanded, taxonomic expertise will become ever more evident—as will the costs of failing to do so.

A poster summary of ‘red list’ report. (Click for hyperlink to source)

The trend toward accepting expedient, molecular-based taxonomy as a substitute for knowledge- and hypothesis-based, so-called ‘descriptive’ taxonomy, is more of a get-rich-quick scheme than a defensible strategy to explore and know our world’s biodiversity. Of course, identifying species is urgent and critically important for conservation and the environmental sciences, but this does not justify abandoning rigorous, fundamental, information-rich science in exchange for quick, easy, and far less informative species determinations. The insect taxonomist Red List report understandably bases most of its argument on the practical need for identifications which, taken out of context, could unintentionally play into the hands of those who argue that DNA barcodes, and other variations on a molecular taxonomy, can deliver ID services faster and cheaper than traditional taxonomy which requires educating a new generation of experts and supporting them to make deep dives into the diversity, distribution and history of taxa.

A better argument is that we need to explore and know species as fully as possible because it encompasses both fundamental and applied knowledge. As a by-product of basic knowledge, we can deliver higher quality services to the environmental sciences; not merely telling species apart, but opening a portal to an abundance of knowledge, information and relevant data. Comparatively easy grant money, in combination with the perception of using cutting-edge technology, is driving decisions that will prove disastrous in the fullness of time—a failure to replace taxon experts, explore species, and prioritize revisionary studies, and shuffling natural history collections off to remote warehouses, creating a physical gap between taxonomists and specimens rich in untapped knowledge.

I, of course, agree with the take home message of the Red List report: We need more taxon experts in Europe… and everywhere else, too. I have some unease about the ranking of expert capacity in the report which seems to be skewed toward sufficient expertise to provide identification services. Given the numbers of species in groups such as Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera, taxonomic capacity isn’t anywhere close to adequate in any nation, or collectively for Europe or the world. That is, if the goal is to actually know species of these orders rather than simply identifying frequently encountered ones.

It would be interesting for the taxonomic community to produce a report that is a hybrid of this Red List of expertise and Arthur Chapman’s study contrasting existing knowledge of species with estimated species numbers. Given that tens of thousands of species are going extinct each year, and the number of experts actively engaged in taxonomy is woefully insufficient and decreasing, it would be timely to produce a Red List of taxonomic ignorance (or, if you prefer, knowledge), highlighting the degree of deficiency of knowledge of taxa. Birds would be one of very few taxa for which something approaching full knowledge exists, but even there a huge amount of work remains to critically test existing species hypotheses, flesh out knowledge of the morphology and natural history of each species, and bring classifications fully in line with phylogeny. And the most species-rich taxa on our planet all deserve a warning of profound ignorance. Taking insects as an example, and by no means the most extreme one, current knowledge accounts for no more than 25% of the estimated number of living species—and the veracity of that estimate may itself be seriously questioned.

The public has little appreciation for the depth of our ignorance about life on Earth. And biologists in general have been lulled into complacency. Severe ignorance of species has existed so long that it is now accepted as a fact of life.

Biologists simply tolerate the assumption that we do not, and never will, know most species on our planet and focus instead on drilling down, almost at random, here and there, to create islands of knowledge in a sea of ignorance, while ignoring the clear, present, and wholly realistic opportunity to complete a planetary-scale inventory of every living thing in a matter of decades.

Biologists simply tolerate the assumption that we do not, and never will, know most species of planet earth and focus instead on drilling down, almost at random, here and there, to create islands of knowledge in a sea of ignorance, while ignoring the clear, present, and wholly realistic prospect of a planetary-scale inventory of every kind of living thing in a matter of decades. A lack of vision for the possible, a failure of imagination, a hesitancy to undertake such a taxonomic inventory, while the possibility remains to do so, would be among the greatest scientific tragedies of all time—imposing permanent ignorance on humankind, eliminating the possibility of deep understanding of life’s diversity and history, and disregarding biomimetic clues for creating a brighter future for biosphere and civilization.

A Red List of taxonomic knowledge, by exposing areas and degrees of ignorance, could highlight both what we know, and what we do not yet know, by ranking our relative ignorance taxon by taxon, and geographic area by area. Such a report should be nuanced. At a crude level, it would contrast, as the Chapman report did, known versus unknown species. But it should also rank the general level or depth and quality of knowledge of species within taxa. A vast number of ‘known’ species have only been named and minimally described and are in fact little-known, while a rather small number have been described in substantial detail. The challenge is not merely to complete a list of our world’s species, but a compilation of as much knowledge about them as is possible, before millions are extinct. One metric of the extent to which we are addressing this ignorance would be the number and frequency of taxonomic revisions and monographs; the gold-standard studies that include detailed descriptive information as well as critical tests of hypotheses about homologies, species and relationships. Another, a ratio of the number of active taxonomists to estimated number of species, as well as the rate of species discovery. Simply demonstrating that species exist as, for example, with a DNA barcodes, would receive a severe red listing because of the profound lack of knowledge about species themselves. DNA barcodes are quite literally the least that we can do to redress our ignorance about species, and at a time of accelerated extinction we should expect and insist on much more.

The preamble to such a report, to provide context, would naturally include the service implications and benefits to conservation, environmental sciences, and the world economy, but should place emphasis on the growth of fundamental knowledge of biodiversity and evolutionary history. Such basic understanding always leads to exciting, impactful, and unforeseeable advances which go far beyond meeting current needs for identifications and basic information.

An inventory of all species, including a description of the results of evolution’s history at the granularity of characters, is as fundamental to our understanding of self and world as is a map of the planets and stars, a table of the elements, or an account of the laws of physics. No number of trees hugged, no number of genomes sequenced, can compensate for the depth of ignorance created should we fail to discover and describe, in detail, as many species as possible.

Taxonomists need to be more vocal in demanding support for their unique kind of research and scholarship, actively embracing, but never becoming a slave to, the latest technologies. And they need to become cheerleaders for their own mission, taking their message to the general public and refusing to submit to peer- and financial-pressures to conform to the priorities and expectations of other disciplines. Only by educating the public about the nature and importance of taxonomic knowledge, and refuting the myth that leads fellow biologists to think that any single data source, like DNA, could substitute for quality taxonomy, can we hope to build support for systematics and an all-out species inventory, before it is too late. One step forward would be a status report that makes clear the kinds and scale of challenges faced by taxonomists, including an incredible level of ignorance of species, their attributes, and their remarkable evolutionary history.

Speaking for threatened taxonomists—and species—everywhere, color me red.

References

Chapman, A. 2009. Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World. Canberra: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts.

Hochkirch, A., Casino, A., Penev, L., et al. 2022. European Red List of Insect Taxonomists. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.