If you’re like me, you look forward, during the holiday season, to that rich, creamy concoction we call eggnog or, in olden times, milk punch. The recipe is simple enough, but, presented with scientific names for the ingredients involved, it sounds quite exotic. Combine eggs of the bird Gallus domesticus with secretions extracted from the mammal Bos taurus; add crystals created by evaporating juices squeezed from the stalks of the grass Saccharum officinarum; some ground-up nuts from the Myristica fragrans tree; and top it off with a sprinkling of powder derived from the bark of the Cinnamomum verum tree—and drink up!

Ethnobiologists tell us that these are among the 50,000 or so species of plants, animals and microbes that have been found useful to humans, at one time or another, and that have played a foundational role in the emergence of modern civilization, from agriculture to biomedicine and too many natural products to count. Knowledge of many species predates formal taxonomy and written history. And taxonomy has advanced so far, become so seamlessly integrated into our lives, that we simply trust, when we shop, that we are being sold the species we set out to buy. Many useful species exist in common knowledge and go by vernacular names—we all know a chicken or cow when we see one, and spices like nutmeg have been traded for thousands of years—but just under the surface things can be a bit more complicated. Multiple species sometimes go by the same common name, and for some purposes this may not matter. But in other situations it can be rather important, such as the difference between an edible or poisonous mushroom, or a harmless or poisonous snake.

The nutmeg that flavors eggnog is derived from Myristica fragrans, but there are 172 species in the genus Myristica and, based on my meager botanical knowledge, I could not tell fragrans from the others without consulting appropriate taxonomic publications or experts. The same may be said of cinnamon which is harvested from the bark of Cinnamomum verum, one of about 250 named species in the genus Cinnamomum.

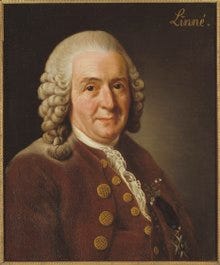

Beginning with Linnaeus, we have taxonomists to thank for the roadmap we follow to find our way around a biosphere populated by millions of species and enjoy the particular natural products that we are accustomed to. An ungrateful society has adopted a “What have you done for me lately?” attitude toward taxonomy. Because people can identify and enjoy the most commonly encountered and sought after species, they feel no further personal need for traditional, information-rich taxonomy and are content to cease describing species and rely instead on snippets of DNA. But this myopia threatens the future prosperity of humankind, as well as that of systematics.

While there is no denying the incredible impact of the 50,000 species various cultures have so far found uses for, that is only the beginning. Those are 50,000 species out of our current knowledge of about two million species. Were taxonomists supported to complete the inventory of life envisioned by Linnaeus, we would know perhaps ten million species. And, if the ratio of useful to total species holds, we would have access to an additional 200,000 “useful” species enriching our lives in ways we cannot yet imagine. But that is a low estimation of the possibilities.

While humans have always been inspired by other species to solve problems and improve the quality of our lives, from draping animal skins over our shoulders to shield ourselves from the cold to taking advantage of antimicrobial properties of Penicillium fungi, this mimetic process has, until now, been a more or less serendipitous one. Someone aware of a problem happens upon a model in nature and puts two and two together.

We now have the opportunity to formalize this process of being inspired by other species, to be more intentional and successful in such biomimetic problem-solving. The emerging field of biomimicry holds the best hope for humans to adapt to a rapidly changing world, mitigating or overcoming a growing list of challenges to our survival, comfort and prosperity. As in the past, taxonomy will play a necessary and central role in the success of biomimicry. It is descriptive taxonomy that documents the detailed attributes of species from which we may imagine applications. It is taxonomy that allows us to identify species and thus locate them in the field when they become of interest. And it is taxonomy’s phylogenetic classifications that permit us to identify a useful attribute in one species and predict where to look, among other species, for similar, and possibly better, versions of the same property or structure.

While the fundamental aim of taxonomy to know, describe and classify all species is a goal in midstream, with millions of species yet to be discovered, the powerful synergy of taxonomy and biomimetic innovation is in its infancy and we have only begun to realize its transformative potential. While simply knowing species, and thus understanding our world and its origins, is justification enough to support taxonomy, those who require a more pragmatic or lucrative argument, to answer the question “What’s in it for me?,” need look no farther than biomimicry. It is critical that we recognize that most of the properties of species which will inspire us to solve problems and meet challenges are not readable from a DNA sequence. Unless we invest in descriptive taxonomy, i.e., revisions and monographs, we will remain ignorant of most knowledge of species that could transform how we live. Molecular data has an important role to play, of course, but so too does the continued description of the incredible diversity of species.

Here's to the incredible adventure of species exploration and discovery set in motion by Linnaeus, to the fantastic impacts of taxonomy on science and society, and to mining the diversity of species through biomimicry for ideas with which to solve the problems we face and create a better future. A toast to the incredible taxonomic enterprise conceived by Linnaeus and its completion! Barkeep, tankards of milk punch for the house—don’t skimp on the nutmeg or cinnamon, and be lively!

References

Benyus, Janine. 1997. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. New York: Morrow.

Wheeler, Quentin. 2024. Species, Science and Society: The Role of Systematic Biology. Abingdon: Routledge.